Alejandro Werner[/caption]

Alejandro Werner[/caption]

(Versions in Español and Português)

It’s been a rough start to 2016, as seen by the recent bouts of financial volatility, stemming from uncertainties related to the slowdown in China, lower commodity prices, and divergent monetary policy in advanced economies.

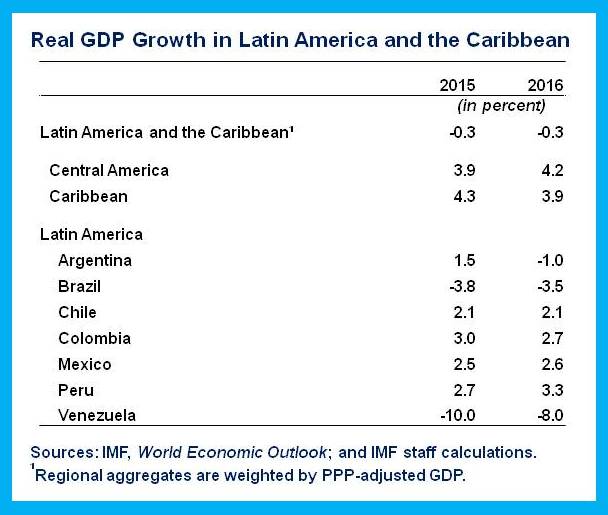

The global recovery continues to struggle to gain its footing, with strains in some large emerging market economies weighing on growth prospects. For Latin America and the Caribbean, growth in 2016 is now expected to be negative for the second consecutive year—the first time since the debt crisis of 1982–83, which triggered the “lost decade” for the region (see table).

The regional recession, however, masks the fact that most countries continue to grow modestly but surely. In particular, country specific developments are being determined by the interplay between external shocks and domestic fundamentals. While countries with strong policy frameworks have been adjusting to external shocks smoothly, countries with weaker domestic fundamentals are experiencing significant downturns.

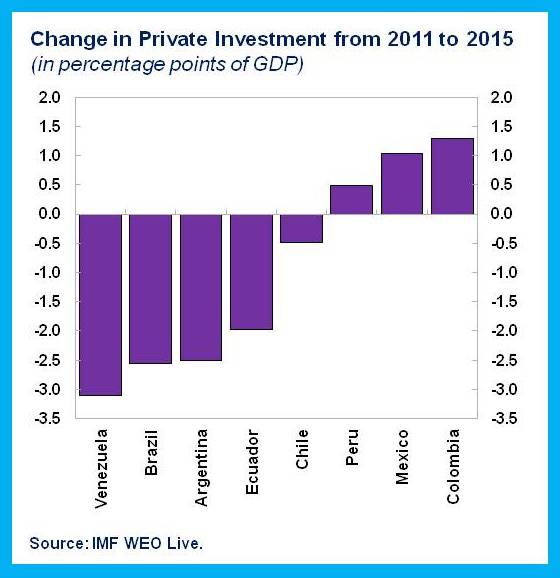

The sizeable decline in commodity prices (about 30 to 50 percent relative to its peak depending on the country) has led to significant losses in export revenues (estimated at around $200 billion for the 7 listed economies). However, the sizes of the terms of trade shocks relative to the sizes of these economies (less than 1 percent of GDP for Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico in 2015 and 2016) are not enough to explain the severity of contraction in some cases. Indeed, our negative growth projection is driven by four countries (Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, and Venezuela), as the decline in commodity prices in combination with macroeconomic imbalances and microeconomic distortions has led to sharp declines in private investment (see chart).

Overall, over the medium term, growth is expected to remain tepid, highlighting the importance of resolving domestic challenges.

The regional outlook also hides important sub-regional differences. While South America is heavily affected by the decline in commodity prices, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean are beneficiaries of the strengthening U.S. economy and, in most cases, of the oil price decline.

South America

In Chile, Colombia, and Peru, a relatively orderly adjustment process continues, where a policy mix of large exchange rate depreciations, gradual fiscal consolidation, and accommodative monetary policies have staved off contraction. The foundations for growth remain in place, including sound policy frameworks, credible institutions, healthy financial markets, and favorable foreign borrowing costs. However, potential growth is expected to be lower given that the transition to more diverse sources of growth will likely take time. In Bolivia, growth also remains strong, but faces risks from rising public debt and the current account deficit.

In Brazil, a combination of macroeconomic fragilities stemming from slow domestic adjustment, a wide-reaching scandal involving government and corporate officials, and political problems have paralyzed investment and dominated the economic outlook. Following a sharp contraction of 3.8 percent in 2015, output is expected to fall a further 3.5 percent in 2016—the largest total contraction since 1981–83. Unemployment has risen sharply, and inflation is in double digits. Political dysfunction continues to delay the adoption of a credible fiscal strategy to keep public debt on a sustainable path, which has prompted rating downgrades and increased financing costs. Although exports are now beginning to show signs of strength with the real depreciating sharply, resolution of political and policy uncertainty is essential to an eventual return to positive growth.

In Venezuela, longstanding policy distortions and fiscal imbalances were already having a deleterious effect on the economy before the collapse in oil prices. These problems worsened as falling oil prices triggered an economic crisis, with an expected fall in output of almost 18 percent over 2015 and 2016 (the third sharpest decline in the world). A lack of hard currency has led to scarcity of intermediate goods and to widespread shortages of essential goods—including food—exacting a tragic toll. Prices continue to spiral out of control, and we expect inflation to rise to 720 percent this year, from a world-high inflation of about 275 percent in 2015.

In Argentina, the new government has started an important transition to correct macroeconomic imbalances and microeconomic distortions. Significant steps towards this transition have been taken by eliminating restrictions on the foreign exchange market, removing several constraints on international trade, and announcing the main guidelines of the macroeconomic framework, and the partial removal of energy subsidies. The new approach has improved prospects for growth in the medium term, but the adjustment is likely to generate a mild recession in 2016.

In Ecuador, a smoother adjustment to falling oil prices is precluded by macroeconomic rigidities. With continued decline in oil prices and real exchange rate appreciation, we anticipate a recession this year. This also reflects fiscal consolidation measures in 2015 and 2016, tight financing conditions, and the dollarization regime which rules out a monetary policy response.

Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean

Mexico is expected to continue to recover at a moderate pace, supported by healthy private domestic demand and spillovers from a strong U.S. economy. The depreciation of the peso and lower electricity prices should boost manufacturing production and exports. The recent decline in oil prices will have only a limited effect on public finances in 2016 as oil price risk has been hedged for that year. However, if the oil price shock is persistent, it would increase the fiscal consolidation burden in the medium term.

Central America and the Dominican Republic have benefited from the oil price decline, a stronger U.S. growth, and higher remittances, but the recent softening of world coffee and banana prices could reduce this impulse. While tourism-based Caribbean countries also benefit from the low energy costs and recovery in the U.S., declining prices for oil, gold, and alumina have worsened the outlook for commodity-intensive countries in the Caribbean.

What could go wrong?

The increase in U.S. interest rates last December had limited impact on U.S. and Latin American asset prices, confirming that markets had largely priced in the decision. Remaining risks are related to the expected path of interest rates, where uncertainty or sudden revisions could cause the term premium to increase—a source of substantial spillovers to long-term interest rates in the region.

The region remains particularly vulnerable to a stronger-than-expected slowdown in China—a main trading partner for the region—and to further declines in commodity prices.

Closer to home, a further deterioration of the situation in Brazil could lead to a sudden re-pricing of regional assets, as well as reduced demand for exports among trading partners in MERCOSUR.

The recovery in investment could be delayed given high corporate leverage in the region. With medium-term growth expected to remain low, corporations may need to adjust their balance sheets, weakening prospects for private investment.

Policy priorities

Large depreciations have created tensions even for the region’s most well-established inflation targeting central banks. As falling exchange rates raised domestic inflation, central banks held their fire and kept monetary conditions adequately loose to support weak domestic demand. But a continued deterioration of global commodity prices has made depreciations unprecedentedly persistent, causing inflation to remain above central bank targets for prolonged periods, except in Mexico. While clear communication has helped keep inflation expectations well anchored, recent upticks have led central banks to respond with modest rate hikes. With current accounts in deficit throughout the region, further external adjustment will likely be needed, putting further pressure on exchange rates and making the job of central banks challenging, particularly in the absence of aggregate demand pressures.

In a global environment that is expected to remain subdued, we expect the region to grow at a slow pace for an extended period. 2016 will be a time for regional policymakers to err on the side of caution: adjustment should be allowed to continue and buffers should be preserved. The regional outlook will only start to look more promising when the domestic challenges facing the contracting economies have been resolved.